To Train or Not to Train with your Menstrual Cycle

Figuring out how best to achieve your performance edge

Historically, studies investigating athletic performance have focused mostly on male athletes. Knowledge from these studies has been applied to female athletes, but unfortunately, what is good for the gander is not always good for the goose!

Females are different. As Dr. Stacy Sims and others have said so accurately, “Women are not small men”. Our physiology is vastly different from males and thus our nutrition requirements, response to training, and recovery - you name it - require different approaches from what is effective for our male counterparts.

One of the key differences between females and males is the monthly menstrual cycle. We have spent a lot of time in Performance Edge learning about the menstrual cycle, what happens when the cycle changes, and how female hormonal physiology serves as a driver of performance. But how do we use this information to gain that edge in athletic performance?

Menstrual Cycle Phases - Some Physiology

The menstrual cycle can be divided into 3 phases:

Follicular phase: The follicular phase begins on the first day of heavy menstrual flow (Day 1) and ends at the time of ovulation, midway through the cycle (~Day 12-18). During this time, the pituitary gland is signaling the ovary, via follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), to begin the maturation of an egg for ovulation. As the egg develops, there is a concomitant rise in estrogen production by the ovary.

Training implications: During this time the rise in estrogen favors an anabolic (growth) environment for skeletal muscle, increased capacity for glycogen storage, and less dependence on fatty acid utilization and oxidative pathways resulting in less fatigue. Bursts of high-intensity and heavy lifts may be favored during this time.

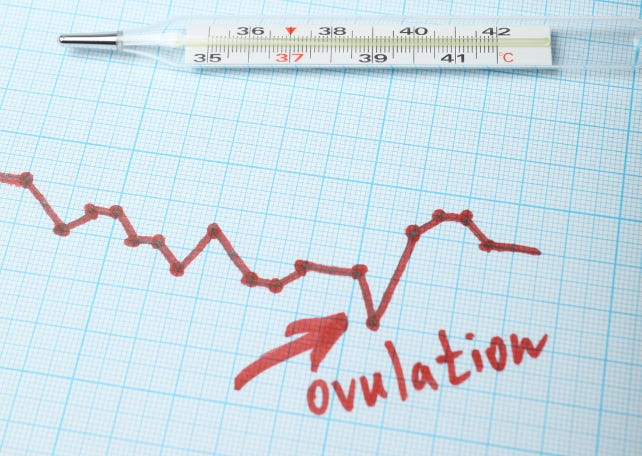

Ovulation: Marked by the surge in luteinizing hormone (LH) production by the pituitary gland which signals the ovary to release the mature egg for pick-up by the fallopian tube (~36 hours).

Luteal phase: Begins after ovulation and extends to the start of the next menstruation. During this time, the rise in estrogen and progesterone production by the ovary prepares the uterine lining for implantation and pregnancy.

Training implications: Although estrogen levels remain elevated following ovulation, Progesterone is now the dominant hormone of the luteal phase. Following ovulation, there is a rise in basal body temperature which can result in a subjective feeling of increased exertion. Progesterone is a more catabolic (breakdown) hormone and antagonizes the effects of estrogen on glycogen storage and metabolism in skeletal muscle and may increase dependence on fatty acid utilization and oxidative pathways. The progesterone dominance of the luteal phase may also blunt protein synthesis in the skeletal muscle impacting muscle repair and recovery. Increased attention to protein intake and recovery activities may be favored along with more low-intensity, endurance activities.

Does Training with the Menstrual Cycle Improve Athletic Performance?

This is a very hot topic with much debate surrounding it. The underlying basis that complicates this question is the high level of variability among each individual’s menstrual cycle pattern and experiences surrounding her cycle. This high level of variability makes the study of populations difficult because to see statistically significant differences in the setting of high variability, large study populations are needed to achieve statistical power to demonstrate these differences if they exist. Unfortunately, the current research in this area is of low to moderate quality and thus cannot definitively conclude - for or against - any benefit of synchronizing training with the menstrual cycle.

What is interesting is that according to experts presenting at the Female Athlete Conference in Boston, MA this year, 60% of athletes surveyed in a recent study report that they subjectively believe that their menstrual cycles impact their training and performance.

Although the aforementioned studies do not show evidence of a benefit of cycle-synchronized training, Dr. Stacy Sims, a leading expert in exercise physiology and nutrition science refutes these studies in her blog post Cutting Through the Confusion of Cycle-Synced Training.

Training with Awareness of Your Menstrual Cycles

Although the debate over whether there is a benefit to cycle-synchronized training continues, one thing that the experts can agree on is that an athlete’s awareness of her menstrual cycle is greatly beneficial for the following reasons:

Every female’s cycle and the experience surrounding her cycle is as unique to her as her fingerprint.

Changes to her usual pattern of menstruation may signal an underlying physiologic issue that could be negatively impacting her performance and/or overall health.

More than 60% of athletes surveyed in a recent study report that they subjectively feel that their menstrual cycle impacts their training and performance.

Even though population data does not support a recommendation for cycle-synchronized training, the fact that many athletes perceive an impact of their cycle on their performance cannot go unnoticed. Perhaps this is the reason why the debate continues.

Despite no clear consensus on this issue, cycle-synchronized training is another tool in the training “toolbox” for athletes to consider on an individualized basis. For some great resources on how to synchronize training with your menstrual cycle, check out this blog post from Dr. Stacy Sims Nail a PR at Every Phase of Your Menstrual cycle, and this great Podcast appearance with WHOOP! Dr. Stacy Sims Answers Members’ Questions on Training and Menstruation

A Word about Hormonal Contraception

A significant number of female athletes use hormonal contraception. As such, questions have arisen about the potential effects of hormonal contraception on training and performance.

This is a complicated subject because females use hormonal contraception for other reasons than to prevent pregnancy. Some females have painful, heavy menstrual cycles that can leave them on the couch for days. Other females experience irregular menstrual cycles and use hormonal contraception to make uterine bleeding more predictable. Irregular cycles can be anxiety-provoking due to an unexpected bleed during an athletic event. Others may have irregular cycles despite all efforts to optimize energy availability and use estrogen and progestin contraception to help prevent bone loss.

So to make a statement about whether hormonal contraception has an impact on athletic performance, one must consider the underlying reason for using hormonal contraception. If an athlete has heavy painful menses that leave her on the couch for days, it is likely that her performance improves while taking hormonal contraception. For females with otherwise normal cycles who are using hormonal contraception strictly for the prevention of pregnancy, there appear to be some trends regarding the impact on athletic performance.

According to a summary of some recent studies, combined estrogen/progestin hormonal contraceptive pills can blunt gains in muscle size and strength, increase cortisol levels, decrease VO2 max, and increase oxidative stress. Estrogen/Progestin contraception is also associated with an increased risk of thromboembolism (deep venous blood clots). Although rare, these blood clots can lead to life-threatening pulmonary emboli (blood clots in the lungs). But to lend some additional perspective, pregnancy has a risk of thromboembolism that is far greater than the risks associated with hormonal contraception.

Progestin-only contraceptive methods tended to have less of a detrimental impact on performance when compared to estrogen/progestin methods according to some studies. These methods include the “mini-pill” or subdermal implants. Lastly, the progesterone intrauterine device (IUD) (Mirena, Liletta, Skyla, Kylena) affords superior contraception with minimal systemic exposure to synthetic hormones. The copper IUD is also a very effective method that contains no synthetic hormones. Caution must be used with some types of progestin-only contraception due to the risk of bone density loss with extended use.

Another consideration when using hormonal contraception is that bleeding patterns are not a result of ovulation as occurs with the natural menstrual cycle. These therapies add predictability and control over uterine bleeding by suppressing the natural patterns of the hormonal cycle, which can be favorable for the reasons noted above. However, low energy availability (LEA) remains a very common problem among female athletes affecting their performance and overall health, and menstrual cycle changes are a strong correlate that can signal LEA and relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S). When using hormonal contraception, the menstrual cycle is no longer available as a barometer of energy status and can potentially mask this problem unless close attention is being paid to other indicators of LEA and RED-S.

Data are mixed and many would argue, and rightfully so, that there is not enough evidence to advise athletes against the use hormonal contraception for the sake of optimizing athletic performance. Reproductive freedom remains paramount to the well-being and quality of life for any female athlete and should be prioritized in any decision making surrounding contraceptive methods.

In Summary…

Female athletes can benefit from awareness of their menstrual cycles.

The current studies investigating the potential benefits of menstrual cycle-syncrhonized training are insufficient to definitively recommend for or against this practice.

Despite the lack of evidence for performance benefits on a population basis, cycle-synchronized training is a tool that is available for athletic training on an individualized basis.

A significant number of female athletes use hormonal contraception for many different reasons.

There is not enough evidence to recommend against the use of hormonal contraception for concerns over athletic performance, however, some trends in the literature warrant some attention.

Hormonal contraceptive methods can mask natural menstrual cycle patterns and thus mask a key indicator of LEA and RED-S.

Reproductive freedom and quality of life of the female athlete should be prioritized in the decision-making surrounding the selection of contraceptive methods.